Guatemala

Guatemala boasts a variety of growing regions and conditions that produce spectacular coffees. Today, the country is revered as a producer of some of the most flavourful and nuanced cups worldwide.

key facts

Harvest months

November – April

Production volume

3,620,000 (in 60kg bags)

Main regions

Acatenango | Antigua | Atitlán | Cobán | Fraijanes | Huehuetenango | Nuevo Oriente | San Marcos

Common varietals

Bourbon, Caturra, Catuai, Typica, Maragogype, Pache, Pacamara

History of coffee in Guatemala

Some accounts have coffee cultivation in Guatemala starting as early as the mid-18th century, when Jesuits brought coffee plants to decorate their monasteries in the city of Antigua. There are accounts dating back to the early 1800s of Guatemalans drinking coffee. Around that time, a perfect storm of blocked trade routes during the Napoleonic Wars, crop-destroying locusts and the creation of cheaper and longer lasting artificial dyes conspired to cripple Guatemalan exports of Indigo, one of the country’s main cash crops. In order to bolster their failing economy, many people began cultivating coffee as a new cash crop.

For the next 150 years, most arable coffee lands were owned by large landowners of European descent. These landowners employed indigenous people from the highlands, few of whom officially owned their own land, to tend and harvest coffee on large farms. This model, while contributing greatly to existing inequality, also put Guatemala on the global map of coffee production.

Coffee from Guatemala

-

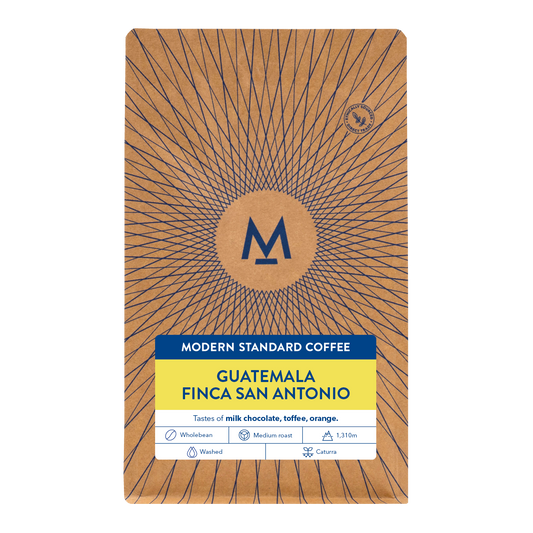

Finca San Antonio

Tastes of Milk chocolate, toffee, citrus acidity.Regular price From £6.00Regular priceUnit price per -

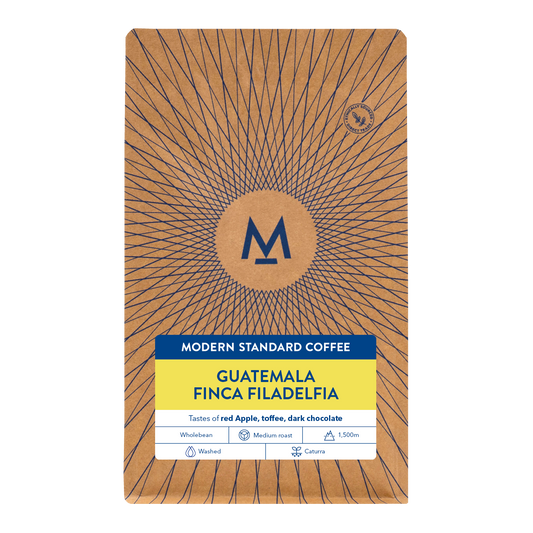

Finca Filadelfia

Tastes of Red Apple, toffee, dark chocolateRegular price From £11.50Regular priceUnit price per

The revolution

In June 1952, during the Guatemalan Revolution, Congress passed Decree 900, also known as the Agrarian Reform Law. The law redistributed land from nearly 1,700 estates to 500,000 landless peasants. The majority of beneficiaries were indigenous people who had not had access to land since the Spanish Conquest in the 1500s. In turn, the law angered many powerful landowners, including the United Fruit Company and the United States, who saw the reform as a communistic threat. The land reform law is often cited as an inciting factor in the 1954 coup d’état that marked the beginning of decades of civil war.

The Guatemalan civil war did not end until 1996, and the violence of the second half of the 20th century hindered the Guatemalan coffee industry significantly. Peacetime stability slowly worked to spread coffee production beyond historic coffee growing regions. Beginning in the 21st century, land where popular crops like macadamia and avocado were once grown came to be replaced with coffee.

Coffee in Guatemala today

Today, the Guatemalan coffee sector is a behemoth. It generates around 40% of all agricultural export revenue and almost ¼ of the population is involved in producing the 3.6 million bags of coffee Guatemala exports each year.

Guatemala’s strictly hard beans (those grown above 1,350 meters above sea level) are considered to be among the world’s best coffee. In particular, beans grown on the southern slopes of the country’s many volcanoes are considered highly desirable. Regional blends from areas like Atitlan and Huehuetenango are pursued with similar fervor as single farm lots from Antigua.

Guatemala’s stellar coffee reputation is a combination of the right environmental conditions and a strong focus on cultivation and processing methods. Coffee is widely cultivated and grows in 20 of the 22 departments in Guatemala. High altitudes, consistent rainfall and mineral-rich soils make coffee an excellent crop across much of Guatemala. The nearly 300 unique microclimates means that Guatemalan coffees boast a diverse range of flavors.

Almost all coffee is Arabica and 98% is shade grown. Nearly all Arabica production is Fully washed, but natural and honey methods are becoming increasingly popular and producing many excellent lots. Many in the country are employing experimental processing methodologies, including soaking after washing, and Guatemalan farmers have been at the forefront of greenhouse drying methodologies. Guatemala’s high altitudes, diverse microclimates, consistent rainfall patterns, and excellent cultivation and processing, make for a variety of distinctive types of Guatemalan Arabica coffees.