The overview

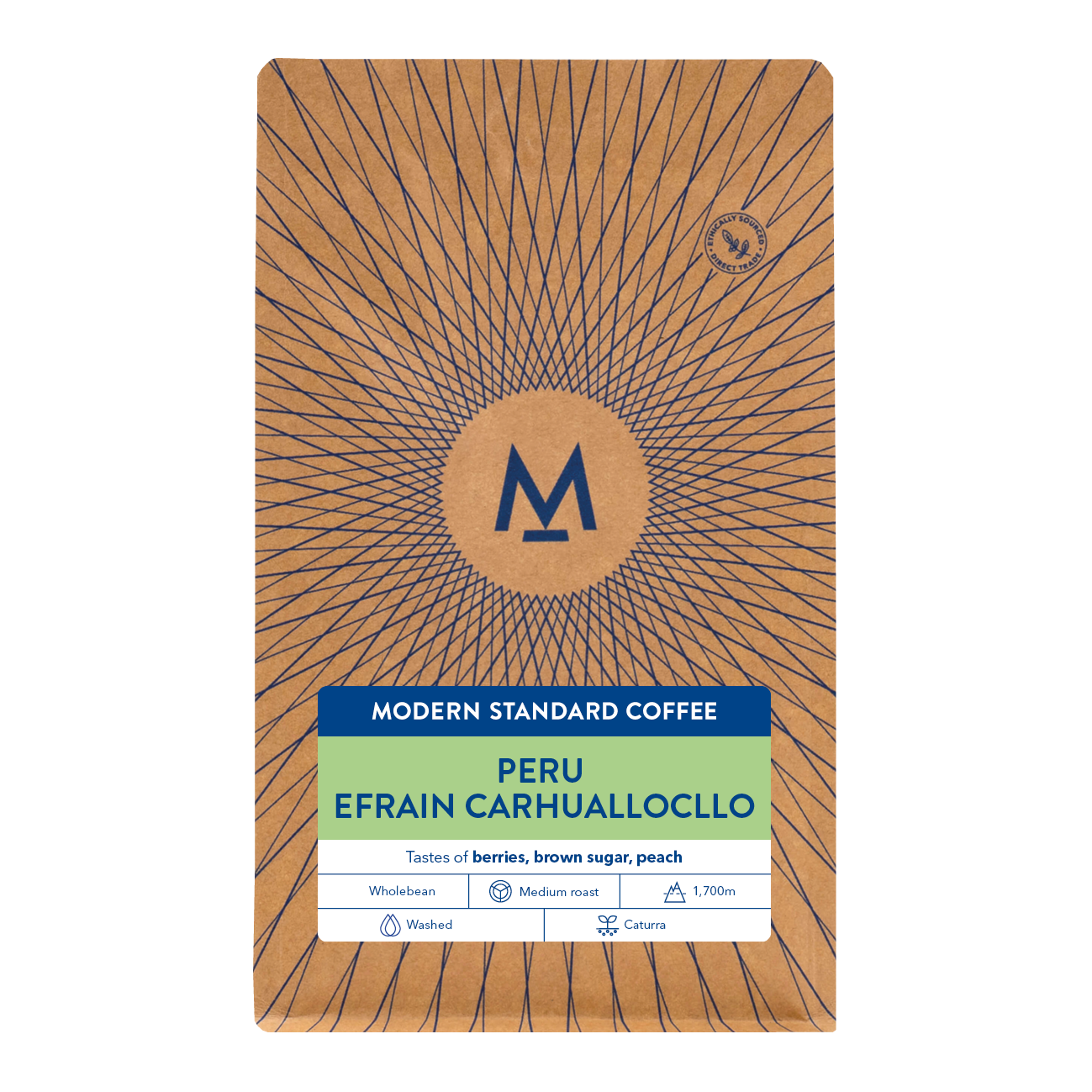

| Countries of origin | Peru |

| Producer | Efrain Carhuallocllo |

| Altitude | 1700m |

| Varietal | Caturra |

| Process | Washed |

The producer

Efrain Carhuallocllo Salvador, a distinguished coffee producer from El Corazon village in the Chirinos district, operates a 4-hectare farm known for its innovation and meticulous management. A celebrated figure in Peru's coffee scene, Efrain secured 2nd place in Peru's inaugural Cup of Excellence competition, earning acclaim for what many considered the best coffee presented. Beyond this achievement, he has garnered numerous local and national awards, making him one of Peru's most lauded coffee producers. Specializing in Caturra (yellow and red) and Geisha varieties, Efrain produced 147 quintales of washed and natural coffee in 2022.

The coffee

Efrain's processing method involves resting the picked cherries for 48 hours, followed by depulping and a 72-hour fermentation in plastic bags. Post-fermentation, the coffee is washed and dried with exceptional care to ensure slow and even drying over approximately 15 days, facilitated by the use of temperature and humidity probes in the drying area.

The district of Chirinos, within the San Ignacio province, is renowned for its high-quality coffee production. Enhanced connectivity and a vibrant town center have made Chirinos a key coffee trading hub. Despite the prevalence of middlemen and a focus on FTO certifications, there's an emerging interest in specialty coffee, led in part by local cooperatives advocating for quality. Nonetheless, many non-cooperative members face market access challenges and limited support for farm improvement. With altitudes exceeding 1700 masl and a heritage of pure Arabica varieties, Chirinos harbors untapped potential for quality enhancement. Strategic investments and minor modifications could enable producers to transcend low market prices, securing better compensation through quality-driven markets.

Why we love it

One of my absolute favourite origin countries is Peru. The high grown coffees offer complexity and sweetness.

Lynsey's Brew Guide

Water: 305g

Ratio: 1:17

I would recommend having this as a pourover, to savour all the complexity this coffee offers, grind it a little finer than usual to make the acidity pop.

Peruvian coffee history

Though coffee arrived in Peru in the 1700s, very little coffee was exported until the late 1800s. Until that point, most coffee produced in Peru was consumed locally. When coffee leaf rust hit Indonesia in the late 1800s, a country central to European coffee imports at the time, Europeans began searching elsewhere for their fix. Peru was a perfect option.

Interest in finding new locations for coffee production coincided with Peru defaulting on a loan from the British government. The Peruvian government gave England over 2 million hectares of land as restitution. The British quickly converted a full quarter of that land into agricultural production and contributed to increasing exports.

Regions of Peru

Today, coffee production is widespread along the eastern slope of the Andes; however, production is concentrated in three main growing areas: Amazonas, San Martín and Chanchamayo. Coffee production previously was most pronounced in Chanchamayo (Central Highlands), which used to produce around 70% of the country’s total crop. The arrival of Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR) had a devastating impact on the region’s production, which has still not recovered.

Currently, the northern highlands of the Amazonas and San Martín regions now account for around 47% of national production. In recent years, many warehouses and mills have opened in Amazonas, San Martín and Cajamarca, further reinforcing this trend.

Farmers in Peru usually process their coffee on their own farms using the Fully washed method. Cherry is usually pulped, fermented and dried in the sun. Traditionally, smaller farmers would use tarps laid on the ground or under the roof of their homes. Increasingly, cooperatives are establishing centralized drying facilities – usually raised beds or drying sheds where members are encouraged to dry their parchment. Some farmers are beginning to adopt these practices on their own farms, and drying greenhouses and parabolic beds are becoming more common as farmers pivot towards specialty markets.

After drying, coffee will then be sold in parchment to the cooperative. Producers who are not members of a cooperative often have the opportunity to sell on to cooperatives, as well.

The remoteness of farms combined with their small size means that producers need either middlemen or cooperatives to help get their coffee to market. Cooperative membership protects farmers greatly from exploitation and can make a huge difference to income from coffee. Nonetheless, currently, only around 15-25% of smallholder farmers have joined a coop group.